This blog is about the early wall paintings at Kinneil House, West Lothian, Scotland, based on a talk given to the Friends of Kinneil, partly about how they were restored, and came to look as they do today, and about what they may have meant in the sixteenth century. The paintings are a very rare survival, and we don’t know if similar paintings were usual in houses of the period, or if as seems possible these had a specific meaning and reference for the owner.

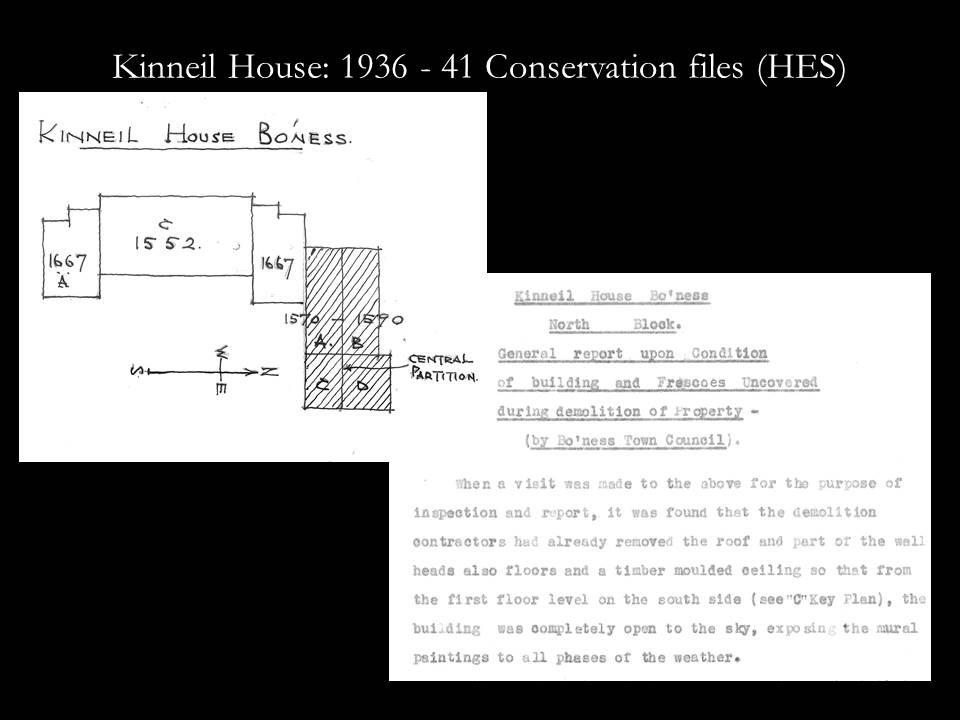

You may know the 1941 article by JS Richardson describing the painting in the Proceedings of Antiquaries. There are also over a hundred photographs from the 1936 restoration, some online, and Historic Environment Scotland’s Conservation Centre has more, with three typescript reports by the lead conservator John Houston which add important detail.

When the older paintings were discovered, the ceiling in the room with the Samaritan painting, known as the parable room, had been taken away to Muirhead near Glasgow to be sold as architectural salvage. The panelling had also been removed, and the some of the plaster had fallen away revealing the glimpses of the Samaritan scenes. After protection from the weather with tarpaulins, the ceiling was restored first. Missing pieces of the moulding were made with old oak brought from Caroline Park in Edinburgh (painted beams discovered at Caroline Park are displayed in the shop at Abbey Strand, Holyrood). Conservation of the painting consisted of a long process of carefully removing more recent plaster, filling the holes hacked into the painting to key in later plaster, and some (limited) tinting and retouching on the new plaster. Windows and doorways were restored according to archaeological findings.

The conservators noted that the frieze of painted grotesque work with a red background around the top of the Parable room had never been plastered over. It must have been covered by a wooden cornice board as part of the later panelling, or perhaps by the wooden ceiling, if that is actually later than the wall-paintings. It is difficult to be certain on this point, there are only three photographs showing this detail before a new floor and restored ceiling was put in.

Piecing the wooden ceiling together as a jigsaw was a challenge, because there were no photographs. Removing later plain paint took six weeks.

Richardson also mentions painted boards found in the house, some surviving, some burnt. The original location of these is unknown. When the work was finished, the Ministry made a display of conservation work upstairs including elements salvaged from Carnock House near Stirling in 1941, which can add to confusion, but luckily the documentation survives to identify these items.

The painting found in the stone-vaulted ‘arbour room’ was more complicated, here there was another scheme of 1620, possibly painted for Anne Cunningham Marchioness of Hamilton by Valentine Jenkin. Her heraldry is prominent in one window (with the Cunningham rabbits), and may have been paired with her husband’s arms in the other window, which was enlarged and blocked destroying the older decoration.

An early photograph shows the painted panelling of the first scheme ending abruptly after six and a half panels in a blank white space. This could have been within an internal porch, a feature frequently found in Scottish inventories and called a “portal door”.

The door in 1620 went out either into the gallery or second hall (now open to the sky), or to the new stair, and not to the ‘parable room’. This bechamber had already lost its immediate connection to that chamber and the entrance hall. So the room use had changed quite radically before any surviving inventories were made.

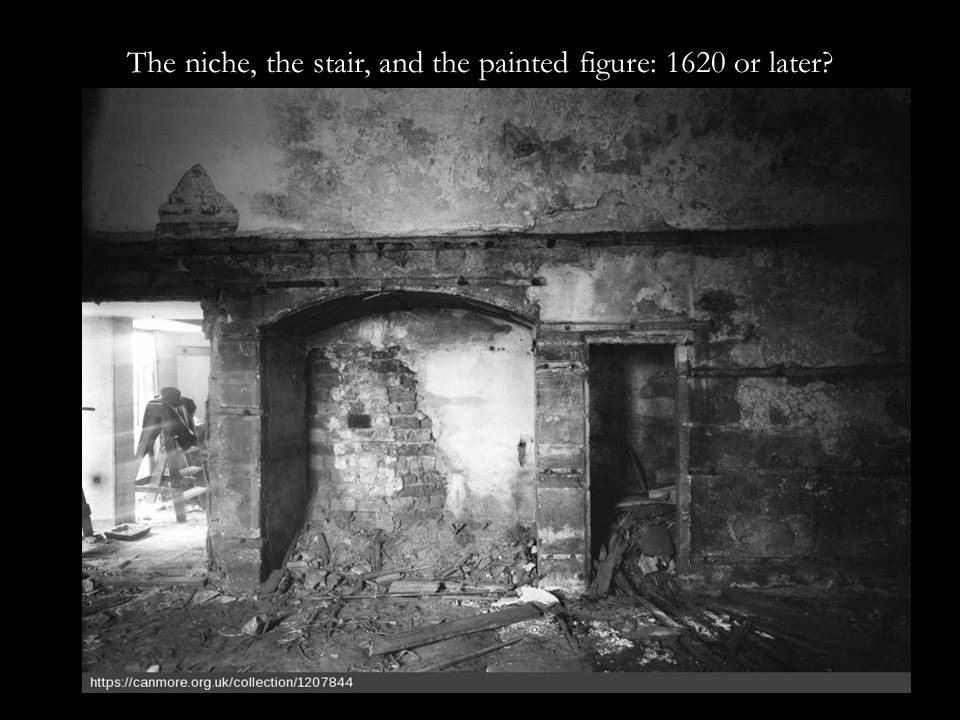

The dating sequence of the arbour room is difficult, and an early photograph doesn’t help much, but it shows that some of the back of the niche is of brick, a part of the stair that was not part of the first build of the wing. So it is not very clear what the niche was, or how old it was, and its function may be doubtful. Richardson called it a buffet recess.

The painting in the niche could date from before the stairwell broke through. It shows a figure spinning, presumably Eve, though this figure is naked, and might have been paired with Adam.

The windows and doors were restored so some areas of the painted panelling are new, and there are blank areas in the parable room. Both painted schemes in the arbour room were left visible, interpreted by the conservators, and both have restoration, so what we see is a visual interpretation of what survived in 1936.

Destruction

One issue with dating the paintings are the two reports of the house being damaged or destroyed. In February 1560 when the former Regent Arran or Duke of Chateherault had become a leader of the Reformation party, French troops led by Henri Cleutin d’Oysel attacked the house, killing three people, but found the house empty with nothing to plunder, and burnt everything in it. Our informant is Thomas Randolph alias Barnaby who had rescued Young Arran from France in 1559.

Perhaps this means that contents, the woodwork was taken out and burnt, and the unusual and hard-to-explain state of the window surrounds may be due to this incident. In both painted rooms and the adjacent hall the plaster stops neatly short of edges of the window surrounds, yet the earliest paint scheme is continued over the stone. Wooden frames may have covered these edges at first, ripped out and burnt by the French troops in 1560.

Ten years later Regent Lennox took action against the Hamiltons after the assassination of Regent Moray at Linlithgow by Matthew Hamilton of Bothwellhaugh. The earl of Morton wrote that Kinneil and the Hamilton lodging at Linlithgow were being destroyed with gunpowder, that this was planned.

But John Lesley, Mary’s secretary, complained to Elizabeth, only that Regent Lennox had taken away goods belonging to the earl and his tenants at Kinneil. Arran, Chatelherault’s own schedule of complaints later in the year only mentions spoiling the barony, the lands. A servant was shot through both thighs, a deliberate wounding, but there was no mention of the destruction of buildings.

Demolishing buildings was expensive and expert work, and would have left more trace in the records, so it is doubtful if Kinneil was damaged then.

The paintings could date from Regent Arran’s time, and possibly before or at the time of the Reformation.

Friar Mark

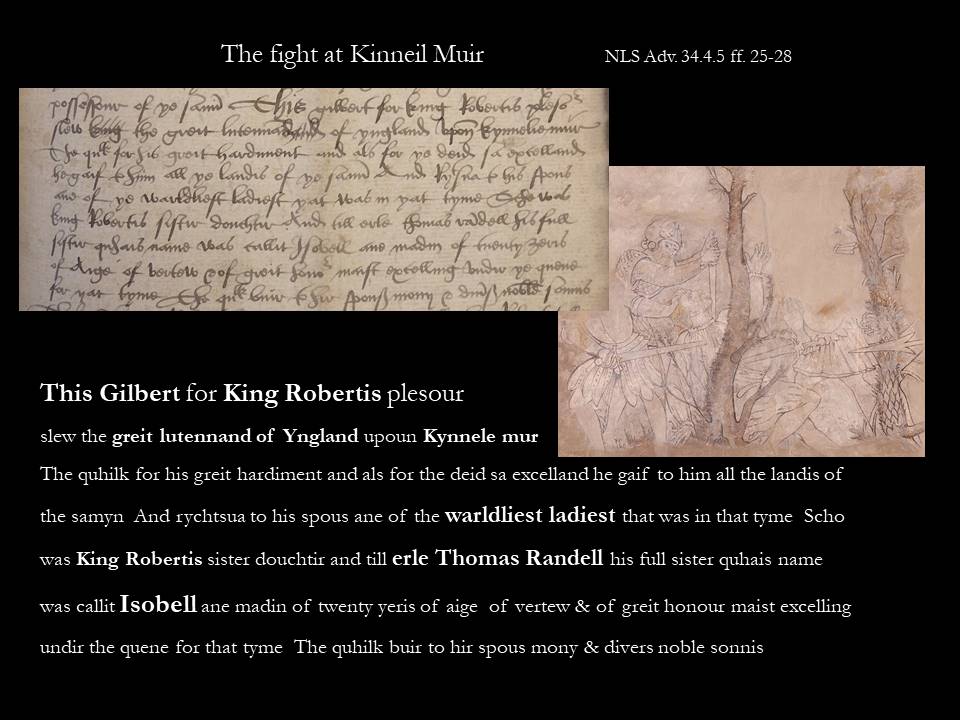

Regent Arran had a short history of the family made or compiled by the Dominican Friar Mark around 1550. This tells the story of Gilbert Hampton and his son Walter Hampton, very loosely based on the founders of the family in Scotland. You can read Friar Mark’s History here, in the original Scots.

The Hamiltons were supposed to be courtiers of Robert the Bruce and Edward I in England. Robert the Bruce gave the Hamiltons land and their coat of arms. They were very manly and had red hair, Robert the Bruce thought a lot of them, and Gilbert spoke at Robert’s funeral, giving some useful ideas about what made a just and rightful king, a commentary on the situation of the 1550s (or perhaps slightly earlier) rather than 1314.

If the paintings had political reference in 1560 then they may have been aligned with Friar Mark’s History.

Slaughter at Kinneil Muir

The history particularly emphasises Kinneil. Walter who had been with English garrison at Bothwell, killed Aylmer de Vallance which pleased King Robert, so Robert gave him the lands of Kinneil and a royal princess Isobel, who was a wardliest ladiest, presumably one of the loveliest ladies in the world, though you can’t be quite sure.

This doesn’t match up with history or genealogy, but it isn’t so far off either, and performs a kind of historical backdrop, emphasising how great the Hamiltons and how they came to have a house here in the East of Scotland.

This Gilbert for King Robertis plesour

slew the greit lutennand of Yngland upoun Kynnele mur

The quhilk for his greit hardiment and als for the deid sa excelland he gaif to him all the landis of the samyn

And rychtsua to his spous ane of the warldliest ladiest that was in that tyme

Scho was King Robertis sister douchtir and till erle Thomas Randell his full sister quhais name was callit Isobell ane madin of twenty yeris of aige of vertew & of greit honour maist excelling undir the quene for that tyme

The quhilk buir to hir spous mony & divers noble sonnis

Friar Mark describes the Hamilton arms

The story returns to the subject of Kinneil moor to explain the features of the Hamilton coat of arms:

sic ane hie act to slay the greit luftenand of Yngland with sa greit spireit of manheid

for the quhilk King Robert gaif till him his armis till weir in Scotland

Thre sinkfuilzeis in ane bludy field

the sinkfuilzeis of the hous of Southe Hamptoune

The reid field be slauchter donne be him

The verranence in taiking he was ane man of weir

The saw was eikit be the first Lord Hamiltoun

And the schipe be the first Erle of Arrane his soun.

The mention of the ship and first Earl, Chatelherault’s father, shows that the text is fresh to the 16th century, and not ancient.

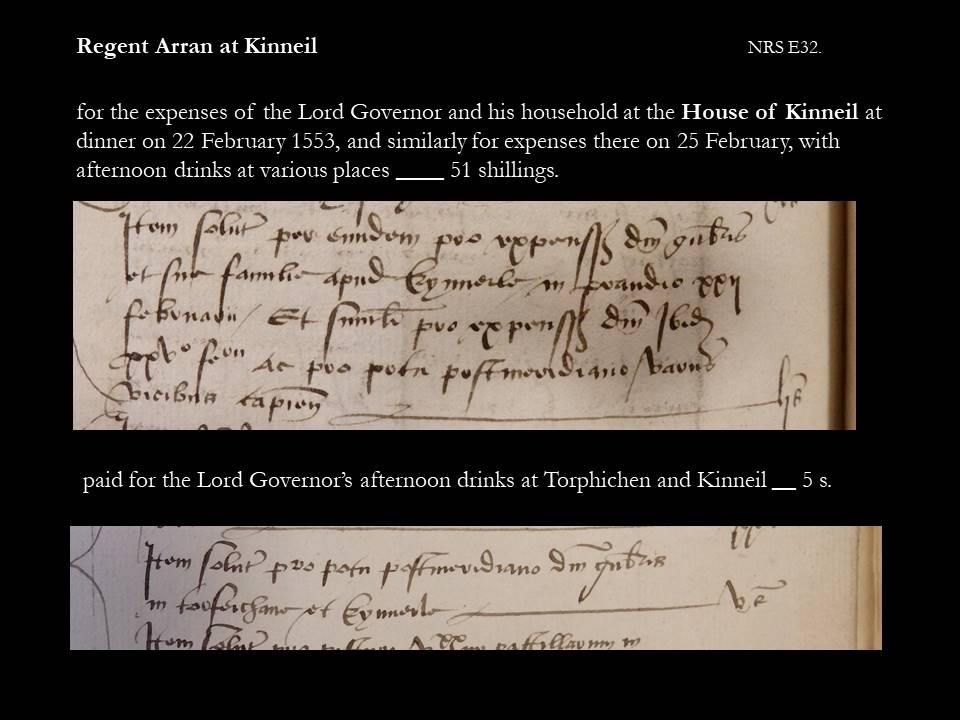

Regent Arran at Kinneil

Despite this emphasis on Kinneil, Regent Arran was quite busy, and didn’t come to Kinneil all that often, at least not with the whole Regent’s court. We know this because the official kitchen account survives in duplicate and gives a lot of detail of what was eaten on a daily basis, with soap, coal, candles and napkins, almost always not at Kinneil.

What we do get are snap shots of visits, of dinners or lunches, and that fleeting afternoon meal: post-meridian drinks. So he came to Kinneil for fun, and to see his builders, and give the builders their tips or bounty payments, as recorded in the treasurer’s accounts.

It is possible that Margaret Douglas, Lady Governor lived here, but the accounts don’t say so. After 1554, when Mary of Guise became Regent the official records stop, and we have only hearsay about Arran’s movements.

There was a deer park at Kinneil, so during the siege of St Andrews Castle deer from Kinneil was sent to Arran’s table at the Priory of St Andrews. The Latin household books of the Regent record the expenses of men sent to Kinneil to fetch deer, and gifts of food sent for his daughter Barbara’s wedding breakfast in Edinburgh. The official, the woodsman or keeper, of Kinneil, George Dilmuir sent two roe and buck for the feast, and as was customary, Regent Arran paid for these gifts.

The Temptation of St. Antony

You may have noticed that apart from the Good Samaritan, most of the scenes show women, not necessarily in a good light. The subjects of these paintings allude to the Power of Women, perhaps a political reference to Mary of Guise, Mary Queen of Scots and the two Tudor queens of England,

However, the painting may more generally represent opposition to justice and rule and the exercise of moral choice. The theme is that of good regiment, opposed to a monstrous regiment, where regiment means healthy ruling and conduct. It happens that the opposition to good regiment was often given a female character in art and allegory

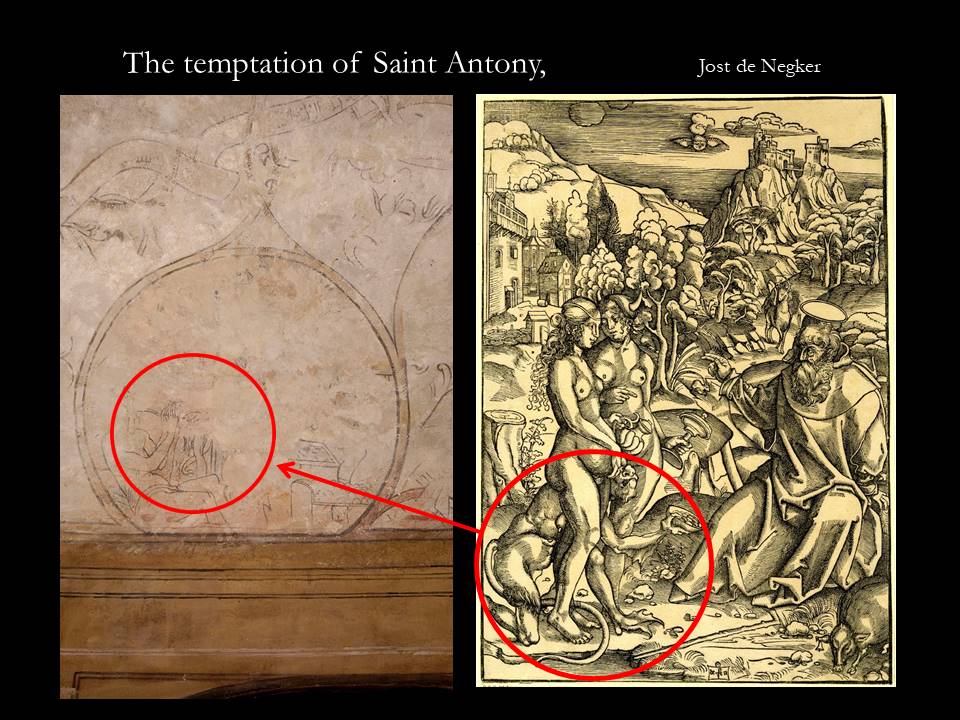

The much damaged Temptation of St Antony is a good example of this: he resists chests of gold coins. It is hard to make out the rest of the scene, but it includes the legs of two women, as shown in this woodcut. Between their legs a suggestive bearded devil offers much gold. Our artist has taken the scene from a similar print.

The temptation of money has a great deal to do with government and legal situation of Regency, and the historian Amy Blakeway is working on these themes.

Abraham & Isaac, David & Bathsheba

The story of Abraham and Isaac isn’t at first sight about the good regiment or women, but the central theme is the willingness to do God’s bidding without question to the utmost, even to kill a son. This obedience is a key part of medieval theory on good rule, with a focus on Old Testament kingship.

David and Bathsheba may be a more obvious example, David abused his royal power for the love of Bathsheba, and caused her husband’s death.

In consequence David and Bathsheba’s first born son died, and so here the two stories are closely linked in this theme of kingship.

David and Bathsheba was also a usual illustration for the seven penitential Psalms in prayer books, another theme of the paintings.

Arran of course, was of course mindful of his own oldest son, once a hostage of Cardinal Beaton, then the Protestants in St Andrews Castle, and in 1559 a hostage for his behaviour in France.

If Arran sat with his back to window, on his right hand was the example of Abraham, whose son was spared, and on the left David & Bathsheba.

Friar Mark on Good Rule

One of Friar Mark’s examples is the story of Saul, who destruction was caused by his choice not by obey God’s commands kill the Abimeleks. In the Friar’s text an idea of elective monarchy is present: that it might be right and just to remove a king or ruler who disobeyed God’s command. This idea is at the centre of the Scottish Reformation, the abdication of Mary Queen of Scots, and the Civil War.

And the paintings at Kinneil illustrate just this theme. And moreover Arran did choose to abdicate his royal power in 1554, receiving and relinquishing financial benefits. No doubt after long deliberation and consideration, with much subsequent regret.

Those that take office and underperform will be ‘objecit’ like Saul, while those who ‘dois it weill salbe honorit’. Friar’s Marks conclusion is written in bolder larger script, just as it could be intoned, or lifted off the page and painted on the wall.

Samson & Delilah

Again in the story of Samson & Delilah, her money payment may be the central character, and the subject an allegory of good and bad motivation – not about the temptress but the temptation from the straight and narrow, available to Arran as French or English gold. Arran is characterised a fence-sitter, or a ditherer, unwilling to commit, and of course in reality he was daily confronted with agonising offers and counter offers.

William the painter

JS Richardson mentioned a painter William the Frenchman, Guillaume, who Anna Mill, the theatre historian, had found in records of the Edinburgh craft incorporation. However, in his article he tried to identify this William with two other men connected with royal tapestry. Anna Mill’s William was lodging in Edinburgh in 1559, not 1549 as appears in Richardson’s article, and perhaps he worked with Walter Binning at Kinneil at that time.

There is much still be discovered about the meanings of the paintings and the intended uses of the palace. Themes and ideas of good rule, obedience, Arran’s changing attitudes, and Friar Mark’s history must be one part of research, along with study of painting itself, the archaeology and the fabric of building.