When Mary, Queen of Scots was deposed and a prisoner in Lochleven Castle, her half-brother James Stewart was made Regent of Scotland. As Regent Moray he needed money to rule and to subdue his enemies, the supporters of his sister. He raised funds by coining her silverware, and asking his treasurer Robert Richardson and his allies among Edinburgh merchants to arrange loans on the security of Mary’s jewels. He also sold some items, including the famous pearls ‘as big as nutmegs’ to Queen Elizabeth. Moray took the ruby pendant known as the ‘Great H of Scotland’ to the York Conference in 1568, but brought it home again, and it remained in the hands of his widow Agnes or Annas Keith.

Mary arrived at Cockermouth a few days after Elizabeth bought the pearls. To oblige her guest, and in deference to wider diplomatic considerations, Elizabeth halted further sales, and Moray’s agent Nicoll Elphinstone of Shank returned to Scotland with unsold items including a slice of unicorn horn. Mary’s jewels remained (for a time) in a coffer in Edinburgh Castle.

In Scotland the political situation did not improve, and the period is now identified as the ‘Marian Civil War’. Moray was assassinated, and some months afterwards his friend William Kirkcaldy of Grange migrated to Mary’s side. This was a disaster for the government established on behalf of her son, since Grange was the commander of Edinburgh Castle.

After a while, John Erskine, Earl of Mar became Regent. He managed to negotiate a truce, called an ‘Abstinence’ and seems from his letters to have been optimistic for some kind of permanent settlement. In September 1572, there was some troubling news from Paris. One of Mary’s emerald jewels had turned up on the open market, and after passing from hand to hand, Charles IX had bought it. The piece had been pledged for a loan three years before, and then forfeited and sold on. This was now embarrasing, because the Regents of Scotland had told Elizabeth and Mary that they would not sell any more jewels. Moreover, the French king’s emerald was a symbolic purchase, a rescue of the Catholic queen goods, that could encourage the hopes of her supporters as a token of commitment to intervene on her behalf.

Mar wrote to the treasurer Robert Richardson outlining the issue. Richardson had created the problem by organising the loans with Moray. A sense of urgency is conveyed by the blotted postscript, – this cause I must rid, must clear away.

The letter is held by the National Records of Scotland, not with diplomatic correspondence, but with other paperwork concerning Mary’s jewel coffer.

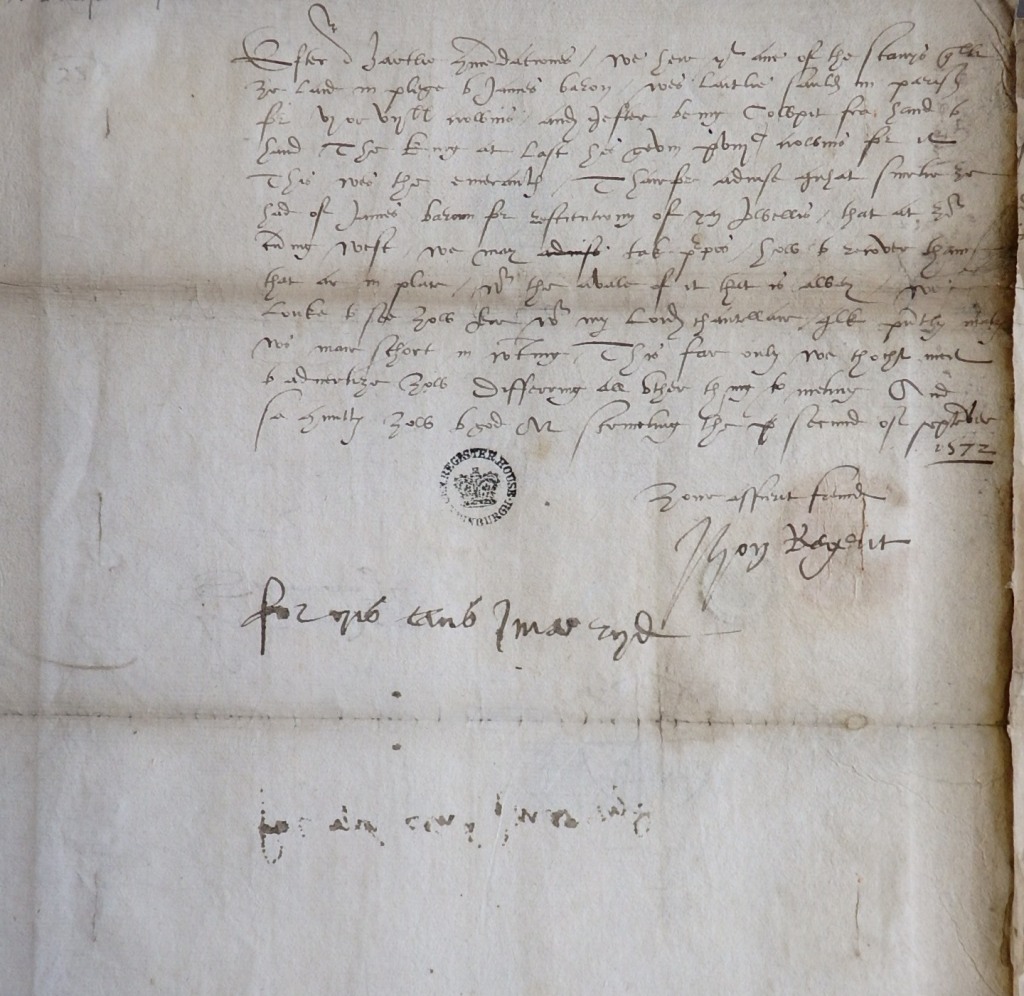

Mar’s letter reads:

After our hartie commendations, we hear that ane of the stanys which ye laid in plege to James Baron wes sauld in Pariss for vj or vijxx crownis and therafter being cowpit fra hand to hand the King at last hes gevin xviict [1,700] crownis for it. This wes the emerants. Thairfor advise quhat suretie ye had of James Baroun for restitutioun of thai jowellis, that at your coming west,[1] we may advise tak purpois how to recover tham that are in plaie,[2] with the avale of it that is away.[3] We louke to see yow heer with my Lord chancellar, which presently maks us mair schort in writing, This far only we thocht meit to advertise yow, differring all uther things to meeting. And so committing you to god, At Striveling the second of September 1572.

Your assurit friend,

Jhon Regent

For this caus I man ryd.

National Records of Scotland, NRS E35/11/24, Regent Mar to Robert Richardson, 2 September 1572.

Other documents tell us a little more about Mary’s emerald jewel. It was pledged to Robert Richardson with other jewels for a loan of £5000 on 17 September 1567. It was then described in Scots as ‘ane uther hyngand tablett with ane emerauld all set in gold’.

The same item apparently appears in Mary’s earlier French inventories as ‘une aultre bague a pendre en laquelle y a une grande esmeraulde a faces mises hors d’oeuvre’, and possibly also as ‘une aultre bacque a pendre en laquelle y a une grande esmeraulde taille a faces et une grosse perle au bout’.

The French word ‘bague a pendre’ means only a pendant jewel. In Scots a ‘tablet’ was a flat piece of jewellery, and the word could describe a locket.

This was a gold pendant, possibly worn on a necklace, featuring a large emerald cut in facets with a large pearl dangling below. The French descriptions give prominence to the emerald and its cut, which presumably was the feature of greatest visual interest and value.

Probably the same jewel, the emerald with a pendant pearl, appears in another unpublished inventory held by the National Records of Scotland (E35/4), made after the death of Francis II which served to demarcate jewels which belonged to Mary or the French crown. Mary was allowed to keep the items marked with a ‘+’.

(I have made a rough transcript of this inventory)

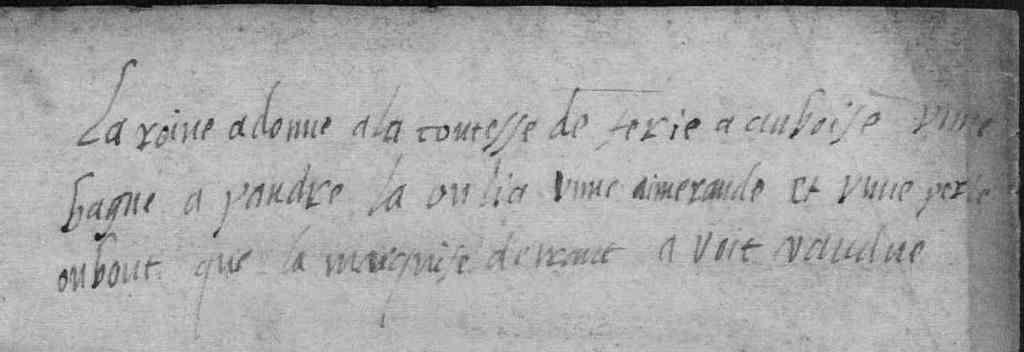

One of Mary’s ladies in waiting noted that Mary had recently given ‘unne bague a pandre la ou lia unne aimeraude et unne perle au bout’ to Jane Dormer, Countess of Feria, at Amboise. It seems, so I suppose, that Dormer was allowed to realise the monetary value of the gift straightaway by auctioning the jewel, ‘a voit vandue’. Mary, it seems, bought it back, a gesture serving to make a gift of cash to the countess more palatable. In more difficult circumstances, Regent Mar was rather more precious about the jewels.

[1] ‘west’ – possibly the directionless ‘ewest’

[2] ‘plaie’ – play, on the market.

[3] ‘avale’ – spending power, available money